Community college student Palmer Luckey made a splash at CES 2013 with his 3D gaming headset, the Oculus Rift—now known as the Meta Quest.

Key Takeaways

- The Nintendo Virtual Boy suffered from poor marketing, misleading portability claims, and an uncomfortable design.

- Health risks and monochrome graphics further alienated potential buyers.

- A high launch price and lack of compelling games sealed its fate.

Today, the Virtual Boy is a curiosity for collectors, a reminder that even the biggest names in gaming aren’t immune to failure—and that sometimes, being too far ahead of your time is just as dangerous as being too far behind.

The Table of Contents

The buzz was so strong that Facebook purchased Oculus for $2 billion. But VR gaming wasn’t a new idea. In fact, Nintendo had already tried its own ambitious virtual reality console in the mid-90s… and it failed spectacularly.

A Brief History – VR Had Already Failed Once Before

Nintendo’s first and only foray into VR came in 1995 with the Virtual Boy, a tabletop “portable” console that promised 3D immersion like never before. Unfortunately, the reality fell far short.

Unfortunately, the reality fell far short.

Released on August 14, 1995 in North America, the Virtual Boy sold roughly 770,000 units worldwide before being discontinued in 1996—making it one of Nintendo’s shortest-lived systems.

Designed by Gunpei Yokoi (creator of the Game Boy), the Virtual Boy is now remembered less for innovation and more for how it missed the mark.

Why Did the Nintendo Virtual Boy Fail?

The failure came down to a combination of poor marketing, hardware limitations, health concerns, and a weak game library. Let’s break down the key reasons why the Virtual Boy never had a chance.

1. Marketing Missteps and the “Portable” Problem

Nintendo’s ads billed the Virtual Boy as a portable console, but the claim was misleading. The device was bulky, awkward, and required a tripod stand to operate—more “tabletop toy” than pocket-sized system.

The design drew comparisons to an oversized View-Master (which arguably worked better). Any device that needs to be stationary on a perfectly flat surface simply isn’t portable in the way consumers expect.

2. Health Risks Scared Away Gamers

From day one, the Virtual Boy carried alarming health warnings. The packaging and manual cautioned players about eye strain, headaches, and even seizures if played for extended periods. Nintendo even included an automatic pause every 15–20 minutes to help prevent visual fatigue.

Parents—already cautious about screen time—were understandably hesitant to let kids use a device that could potentially cause eye problems.

3. Weak Virtual Boy Game Library

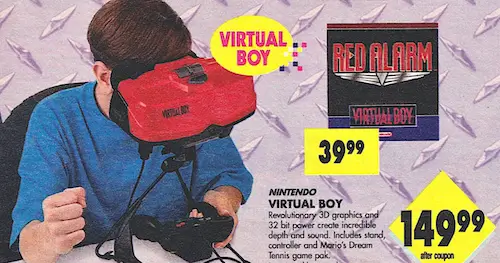

Only 22 games were ever released worldwide for the Virtual Boy, and many felt like quick ports rather than system sellers. Titles such as Panic Bomber and Mario Clash offered novelty but not enough gameplay depth to justify the cost of the hardware.

Flagship launch games like Mario’s Tennis and Teleroboxer showed potential, but the limited 3D effect and monochrome red-and-black graphics left players wishing they were on a Nintendo NES or Game Boy instead.

- As IGN notes in its retrospective on the Virtual Boy, this is not a revisionist look at Nintendo’s most famous failure — the system’s shortcomings were apparent even at launch, from its uncomfortable design to its limited game library.

4. Graphics That Fell Behind the Hype

While Nintendo touted the Virtual Boy’s “cutting-edge” 3D display, the reality was underwhelming. Oscillating mirrors created the illusion of depth, but the visuals were strictly red-and-black monochrome—a choice made to reduce cost and battery consumption.

In an era where the Super Nintendo Entertainment System was delivering colorful, detailed sprites, the Virtual Boy’s visuals felt like a downgrade.

5. Hardware Limitations

Physically, the Virtual Boy was unwieldy. The tripod stand only worked well on stable, perfectly level surfaces. The fixed viewpoint also limited gameplay to a seated position with your head pressed into the visor, making long sessions uncomfortable.

The lack of true portability made Nintendo’s marketing even more questionable. Gamers expecting a “take-anywhere” console were disappointed.

6. Price That Didn’t Match the Experience

At $179.99 at launch in 1995 (over $350 today when adjusted for inflation), the Virtual Boy was expensive for a novelty system with no killer apps.

Nintendo reportedly considered a full-color display during development, but the added cost would have pushed the MSRP beyond $700—putting it well out of reach for most consumers and far above competitors like the $99 Game Boy or $199 Sega Saturn.

Here is an old school launch commercial for the Virtual Boy

▶

▶

Why the Nintendo Virtual Boy Failed — Summary

| Reason | Details | Impact on Success |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Missteps | Advertised as “portable” despite requiring a tripod and stationary setup. | Created unrealistic expectations and disappointed buyers. |

| Health Risks | Warnings for eye strain, headaches, and seizures; automatic pauses every 15–20 minutes. | Discouraged parents and reduced player appeal. |

| Weak Game Library | Only 22 titles; many felt like quick ports (Panic Bomber, Mario Clash) with limited depth. | No killer apps to drive hardware sales. |

| Underwhelming Graphics | Monochrome red-and-black visuals with limited 3D effect. | Looked outdated next to colorful SNES-era games. |

| Hardware Limitations | Bulky design, fixed viewpoint, uncomfortable posture requirements. | Reduced playability and portability appeal. |

| High Price | $179.99 at 1995 launch (~$350 today); a color version would have pushed MSRP past $700. | Poor value versus alternatives like Game Boy or Sega Saturn. |

The Retro Wrap Up & The End of the Virtual Boy

By early 1996, Nintendo had pulled the plug. With low sales, a poor game library, and no third-party momentum, the Virtual Boy became Nintendo’s biggest commercial failure up to that point.

Even its creator, Gunpei Yokoi, acknowledged that the system hadn’t met expectations. In hindsight, the Virtual Boy stands as a cautionary tale: combining limited technology with overambitious marketing is a recipe for disaster.

Sell Your Nintendo Virtual Boy Games

Turn your Virtual Boy collection into fast cash with a trusted retro game buyer.

- Instant online quote

- Fair, transparent pricing

- Fast payment options

Sources:

- Polygon. (2018, May 1). The history of Nintendo’s forgotten console, the Virtual Boy.

- Retrieved from https://www.polygon.com/history-of-fun-podcast/2018/5/1/17308830/the-history-of-virtual-boy-podcast-history-of-fun

Frequently Asked Questions

How many Nintendo Virtual Boy games are there?

- A total of 22 official games were released for the Virtual Boy worldwide, with 14 in North America and 19 in Japan. Some titles were region-exclusive.

How does the Nintendo Virtual Boy work?

- The Virtual Boy used oscillating mirrors to project slightly different red-and-black images into each eye, creating a stereoscopic 3D effect. It was designed for tabletop use with a head-mounted visor.

How much is a Nintendo Virtual Boy worth?

- Prices vary based on condition, completeness, and rarity of included games. Loose consoles can sell for around $150–$250, while boxed sets with games can fetch $400 or more from collectors.

What is the Nintendo Virtual Boy?

- The Nintendo Virtual Boy is a 32-bit tabletop video game console released in 1995 that offered stereoscopic 3D graphics. It is widely regarded as Nintendo’s biggest commercial hardware failure.

What happened to the Nintendo Virtual Boy?

- Poor sales, a small game library, uncomfortable design, and high price led Nintendo to discontinue the Virtual Boy less than a year after launch.

When was the Nintendo Virtual Boy discontinued?

- The Virtual Boy was discontinued in North America in early 1996, only about six months after its August 1995 release.

When was the Nintendo Virtual Boy made?

- Development began in the early 1990s, led by Gunpei Yokoi, and the console was manufactured in 1995 for release in Japan and North America.

When did the Nintendo Virtual Boy come out?

- The Virtual Boy launched in Japan on July 21, 1995, and in North America on August 14, 1995.