From the vibrant arcade halls to living rooms around the world, Sega once reigned supreme in the gaming universe.

But how did this titan, celebrated for iconic characters like Sonic the Hedgehog, transform from a powerhouse of innovation to a cautionary tale in the industry?

Sega Console History: Why Did Sega Fail? – Key Takeaways

- Sega’s bold marketing and Sonic branding gave the Genesis a strong foothold in the early 1990s console wars.

- Confusing hardware releases like the Sega CD, 32X, and Saturn damaged consumer trust and split the user base.

- Dreamcast was innovative but failed to compete with PlayStation 2’s DVD support and stronger third-party backing.

- Internal conflict between Sega of America and Japan weakened execution and created fragmented messaging.

- Sega pivoted to software publishing after the Dreamcast’s failure, becoming a key developer in the modern gaming world.

Join us as we dive deep into the thrilling highs and devastating lows of Sega's journey, exploring the key decisions and missteps that led to its dramatic fall from grace.

The Table of Contents

Sega's Ambitious Challenge: The Rise Against Nintendo in the Console Wars

Sega's journey in 1940, long before the company became a key player in the video game industry. The late 1980s and early 1990s were important in shaping the legacy of Sega.

This time is often remembered for the fierce competition between game consoles, which played a key role in the reasons behind Sega's decline and raises the question: why did Sega fail?

is often remembered for the fierce competition between game consoles, which played a key role in the reasons behind Sega's decline and raises the question: why did Sega fail?

The 1990s was an important time in gaming. Companies like Sega went head-to-head with major players like Nintendo and Sony.

This resulted in an intriguing tale about competition in the console market, where a smaller company managed to surpass a larger competitor. However, ultimately, the smaller company did not achieve long-term success.

- In 1990, Michael Katz, the president of Sega of America, said that the company aimed to capture 50% of the console market. At that time, they only had a 6% share.

This strong statement showed the desire of the underdog to make changes. However, it also caused conflicts with Sega Japan, which wanted to stick to more traditional business methods.

Internal Conflicts and Strategic Shifts: Navigating the Path to What Happened to Sega

- Eventually, Tom Kalinske took over for Katz. Kalinske had been the president of Mattel. He worked well with management in Japan.

- Seeing the need for a strong mascot to compete with Nintendo's Mario, Kalinske started a new marketing plan. This was designed to help Sega become more popular in the tough gaming market.

- This bold decision helped make Sonic the Hedgehog an important character for Sega. It showed the creative energy that first attracted gamers and helped the company succeed.

Sega's Competitive Strategy in the 1990s Console Wars

- In the summer of 1991, during the Summer Consumer Electronics Show, Nintendo launched the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), enhancing the beloved NES with impressive 16-bit graphics and a vast color palette of 32,768 colors.

- With iconic characters like Mario leading its charge, Nintendo seemed unstoppable. However, Sega's Genesis (known as Mega Drive in Japan) entered the arena as the underdog, showcasing its own innovative title: Sonic the Hedgehog.

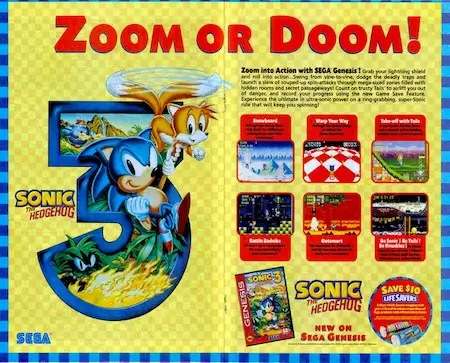

The Birth of Sonic the Hedgehog: A Cornerstone of Sega's Success

- Sonic the Hedgehog was created by artist Naoto Ohshima at Sega. He was designed to be a

fast character, which was important for competing in the gaming market.

fast character, which was important for competing in the gaming market.

- "Sonic was designed to be cool and fast—qualities we knew would resonate with gamers," Ohshima explained. "It was all about capturing the spirit of the time."

- This famous blue hedgehog became Sega's mascot and connected with many consumers. Sonic played a key role in Sega's success in the tough video game market, especially for people known as the "Ritalin generation."

Aggressive Pricing and Bundling: The Strategy Behind Sega's Early Success

- Sega of America president, proposed a daring move: to drop the Sega Genesis price to $149 and bundle it with Sonic the Hedgehog.

- Tom Kalinske, former CEO of Sega of America, remarked, "We were the company that challenged the status quo.

- When you look back at the early days of the 16-bit era, we were the underdog, but we were determined to disrupt the industry."

- Despite strong disagreement from Sega Japan, the idea, which arose from a tense board meeting, was finally approved.

- This bold plan worked well, leading to the sale of 15 million Sonic bundles. This was a key moment in the console market and it highlighted how Sega expanded in the gaming industry.

However, this success begs the question: what happened to Sega?

- Even though Sonic the Hedgehog made significant achievements and became well-known, a few mistakes and challenges in the market would soon hurt their place in the gaming industry.

- As Game Industry Journalist Matt Cassamassina noted, "Sega's aggressive pricing strategy and bundling with Sonic was a brilliant move that propelled them into the limelight, proving that innovation can come from even the most unlikely contenders."

- However, the desire that helped them rise also led to problems later on. The problems and management issues within Sega in the 1990s were a big part of the company's decline. These challenges made it hard for Sega to keep up with the rapidly changing market.

Market Dominance: Reaching the Pinnacle of Success and the Prelude to Sega's Downfall

By the end of 1992, Sega was very successful in the video game market. It held a 60% share of the console market in North America. This success demonstrated that the Sega Genesis was a powerful player in the gaming industry.

the console market in North America. This success demonstrated that the Sega Genesis was a powerful player in the gaming industry.

- A big part of this success was the release of Sonic the Hedgehog. Sonic captured the attention of many consumers and helped define Sega's brand.

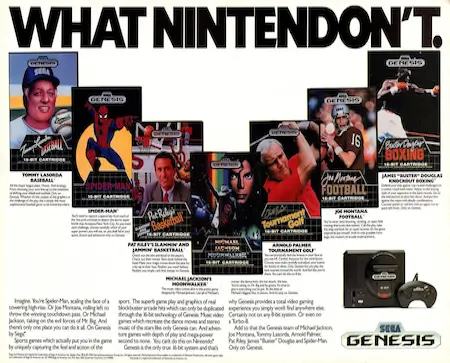

Sega's strategic marketing targeted a more mature audience, contrasting with Nintendo's family-friendly approach. Slogans like "Genesis does what Nintendon't" helped Sega stand out.

- They made Sega a popular choice for gamers who wanted excitement and new ideas.

- The company was one of the first to bundle popular games with their console.

- This helped increase sales and attract more customers.

Despite reaching such a high point in the competitive landscape, this triumph would later prove fleeting. As competition grew and mistakes were made, Sega's strong position in the market started to weaken.

📚 Related Article: The History of 90s Handheld Consoles

Curious how the Game Gear stacked up against the Game Boy? In Lost Gems: Learn the History of Handheld Consoles Before the Game Boy, we examine Sega’s portable ambitions and why they fell short in the handheld wars.

Why Did Sega Fail? The Key Factors Behind the Sega Downfall

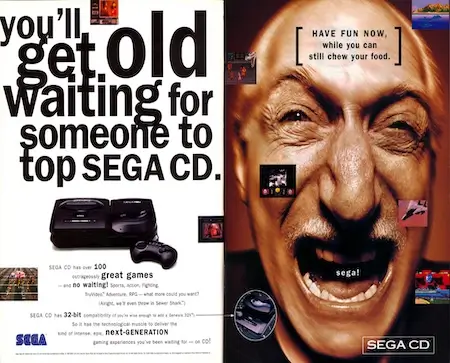

What Started the Sega Downfall?: The Rise and Fall of the Sega CD

One of Sega's critical missteps was Sega's focus on developing console add-ons, starting with the Sega-CD. Scot Bayless, a senior producer at Sega, discussed this issue. He said, "The Sega-CD never really had a reason to exist." We miscalculated the direction we needed to take and lost sight of what our consumers wanted."

Sega-CD. Scot Bayless, a senior producer at Sega, discussed this issue. He said, "The Sega-CD never really had a reason to exist." We miscalculated the direction we needed to take and lost sight of what our consumers wanted."

- This disc-playing device was designed to give gamers immersive interactive movies. However, it did not succeed because its hardware was not powerful enough for consumers.

- The Sega-CD had major issues, such as overheating. This overheating caused test units to break down in various ways.

- Not to mention, the power on/off fuse on the board was infamous for blowing, and these consoles seemed to constantly require re-formatting their internal memory, a process we’ve covered in detail here.

- This loss of reliability harmed Sega's reputation and caused consumers to trust the brand less.

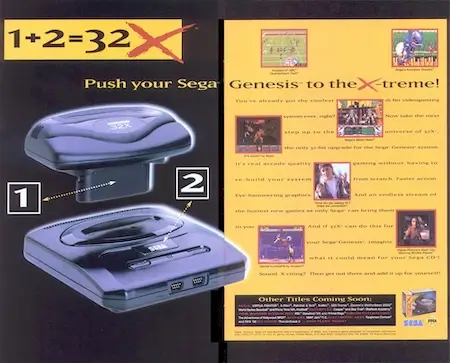

The 32X: A Major player in the Sega Downfall

- Following the hardware failure of the Sega-CD, and the chaotic product launche, of the ill-fated Sega 32X, are often cited as pivotal moments that contributed to the overall Sega downfall.

- The decision to launch the 32X, an add-on designed to enhance the Genesis' capabilities to 32-bit and compete with Atari's 64-bit Jaguar.

- The Sega 32X was sold as a way to make gaming better. However, it ended up being a big problem for Sega and played a part in the company's decline.

Several key issues plagued the 32X:

- Misalignment with Consumer Expectations: Many gamers were confused about this product because it was presented as an add-on rather than a stand-alone console.

- This confusion grew with the upcoming release of the Sega Saturn.

- Limited Game Library: The Sega 32X was released with a small number of games. These games didn’t effectively utilize the 32-bit hardware, which failed to generate excitement for the console.

- Poor Timing: The 32X was released right before the Sega Saturn. Because of this, it was quickly forgotten.

- Ineffective Marketing: Sega's promotional efforts did not effectively communicate the value of the 32X, leaving potential customers uninformed and uninterested.

- Development problems arose because of quick production. This caused a messy development process.

These factors caused many people to dislike the 32X. As a result, it is now seen as one of the worst video game consoles ever made. The mistakes show how crucial it is to plan properly, understand customers, and market well in the competitive gaming industry.

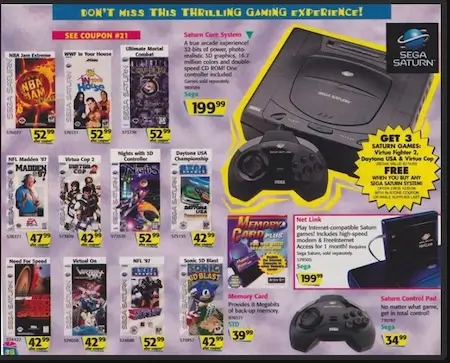

Why did the Sega Saturn Fail - Despite a Strong Game Library

The Sega Saturn did not do well in the gaming market for a few reasons, even though it had a good selection of games.

- The Saturn was released unexpectedly on May 11, 1995. This early launch surprised both retailers and consumers. This limited the early sales and marketing efforts for the console.

- High Launch Price: The Saturn was priced at $399, which was higher than competitors like the Sony PlayStation.

- The Saturn had tough competition from the PlayStation and Nintendo 64. Both of these consoles attracted gamers with new gameplay ideas and strong marketing efforts.

- Limited Support from Other Companies: The Saturn had excellent games made by its own team, but it had a hard time getting games from other developers.

- Development Challenges: The Saturn's design was complicated. This made it hard for developers to make the most of its hardware.

- Sega's marketing for the Saturn was inconsistent. Their efforts did not appeal to customers, which reduced interest in the product.

- Brand fatigue occurred because of Sega marketing blunders with the Sega-CD and 32X.

- Made gamers lose trust in the Sega brand. As a result, many were hesitant to buy another Sega console.

These factors together led to the Sega Saturn's failure. They show how important good timing, strong marketing, and solid support from other companies are in the gaming industry.

Sega's Chaotic Approach: The Fallout of the 1990s Console Wars

- In the 1990s, Sega changed its strategy. Instead of having a clear plan, they reacted to the market.

- This led to a disorganized release of products. The company released many consoles and accessories. These include the Sega Genesis, Sega-CD, Sega 32X, Sega Gear, and Sega Saturn. They did this to attract more customers.

- This scattered approach hurt the market and confused buyers, which was a big reason Sega failed. Without a clear plan, Sega struggled and became less important in the gaming industry during a key time.

Summary of Failures:

- The Sega CD was meant to improve gaming with interactive features. However, it had hardware problems and didn't have enough interesting games. As a result, it did not appeal to many gamers.

- The Sega 32X was an add-on for the Genesis. It confused many buyers and had a small number of games available. Its release before the Sega Saturn made its failure worse, leading to its reputation as one of the worst consoles ever.

- Sega Game Gear: At first, it was a strong competitor to Nintendo's Game Boy among the popular 90s handheld consoles. However, the Game Gear had a short battery life and didn't have many popular games. Its high price and bulkiness made it less appealing to consumers compared to its rival, limiting its market success.

- Sega Saturn: The Saturn had a good selection of games, but it was released early and was priced high. This surprised many buyers. It also faced tough competition from the PlayStation and Nintendo 64. As a result, it struggled to get support from other game developers and didn't do well in the market.

These mistakes show that Sega's unclear strategy and lack of a solid plan caused big problems. These problems lowered the company's position in the gaming industry.

📚 Related Article: Sega vs Sega – The Console Battle Within

Dive deeper into the Sega legacy by comparing two of its most iconic yet troubled systems. In Sega Saturn vs Dreamcast – Which Console Left a Bigger Mark?, we explore their hardware strengths, game libraries, and role in Sega’s final days as a console maker.

Sega's Last Stand in the Console Wars - The Sega Dreamcast

At the end of the 1990s, Sega aimed to improve its place in the gaming market by launching the Sega Dreamcast in 1998. The Dreamcast was a strong and capable console. It was made to compete with newer systems like the PlayStation 2, the original Xbox, and the Nintendo GameCube.

compete with newer systems like the PlayStation 2, the original Xbox, and the Nintendo GameCube.

- The Dreamcast was one of the first consoles to feature online gameplay capabilities, which Microsoft helped develop. This experience with online gaming and network services laid some groundwork for Microsoft's later development of the very first Xbox, which was released in 2001.

- In examining Sega's gaming legacy, a key comparison arises between the Sega Saturn vs Dreamcast. While the Saturn struggled to gain market traction due to various missteps, the Dreamcast initially found success with its innovative features before facing its own challenges.

This new way of online gaming made the Dreamcast stand out from other consoles. It showed that Sega was dedicated to improving the gaming experience.

Coupled with a diverse library featuring titles like: Sonic Adventure, Shenmue, Crazy Taxi, and Jet Grind Radio these advancements sparked hope for Sega's revival.

Why did Sega DreamCast fail? Several key challenges affected the Dreamcast's ability to make money.

- High manufacturing costs made it hard to set competitive prices. Also, past failures, such as the Sega Saturn, led to doubt among consumers.

- As people turned their attention to new gaming systems, especially the PlayStation 2, the Dreamcast struggled to compete.

- The dagger in the heart of the Sega DreamCast was the fact the PlayStation 2 could play DVD's and the DreamCast could not.

In the end, even with its promise and initial success, the Sega Dreamcast disappeared from the gaming scene. This marked the end of Sega's era as a console manufacturer.

Sega's Evolution: From Console Powerhouse to Successful Software Publisher

- Sega faced many problems in the console market. However, the company got a boost from an important investment by Isao Okawa.

- This financial support helped Sega move from making hardware to publishing software. This change let the company use its wide range of popular game franchises.

- Sega focused on popular game series like Sonic the Hedgehog and Virtua Fighter. This helped them adjust to changes in gaming. They found new chances in mobile gaming and digital sales.

- Sega works with independent developers and uses new technologies to keep making successful games. This helps them stay profitable in the competitive gaming industry.

- However, the era of Sega as a console powerhouse has long passed, likely never to return. The tough competition from other companies and the changing gaming market have made Sega a key software publisher. Sega may not lead in making consoles anymore, but Sega's strong history still impacts the industry.

Conclusion: Key Lessons from Sega's Journey in the Gaming Industry and Why did Sega Fail

Sega went from being a leader in the video game industry to a warning for other companies. This change is an interesting example for businesses today. Their journey shows how important it is to adapt to changes in the market and to have a clear plan.

- Poor management and disorganized product launches played a big role in Sega's decline.

- This shows that businesses should act before issues come up, not just deal with them afterwards.

Sega went from being a major player in the gaming world to facing tough challenges. Its story shows how important it is to adapt and plan carefully in a competitive market. As the industry evolves, developers must concentrate on fresh ideas, clear branding, and a solid plan for the future.

Sega shifted from making consoles to concentrating on video games. This change highlights the need to adapt and respond to what customers want. This change shows that to succeed in the gaming industry over time, companies need to be creative, plan ahead, and learn from their past errors.

Share Your Thoughts

- We'd love to hear from you! What are your thoughts on Sega's impact on the gaming industry?

- Did you have a favorite Sega console or game that holds a special place in your heart?

- Please share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below. Let’s start a conversation about the legacy of this important gaming company!

About Us – Trade In Your Sega Consoles & Games for Cash

At The Old School Game Vault, we make it easy to sell Sega Genesis games, consoles, and accessories for fast cash payouts. Whether you're unloading childhood favorites or clearing space, we're here to help.

We buy items from the Sega Genesis console line and other Sega systems — including the Sega Nomad, Sega CD, Sega Saturn, Sega Dreamcast, and more. If you're unsure what's accepted, check out our Video Game Console Selling Guide – Cash In On Your Retro Systems for full details.

Using our website’s search tool, you can quickly get a quote for your Sega gear. We offer competitive prices based on real market demand. For orders over $100, we’ll even send you a prepaid shipping label.

Choose from secure payment options like PayPal or paper check — and turn your old-school Sega hardware into instant cash today.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding the Legacy of Sega

What happened to Sega?

- Sega exited the console market after multiple hardware failures and now focuses on publishing games.

Why was Sega discontinued?

- Sega discontinued its consoles due to declining sales, brand fatigue, and competition from Sony and Nintendo.

Why did Atari fail?

- Atari failed because of poor game quality, market saturation, and internal mismanagement during the video game crash.

Why did Sega 32X fail?

- The 32X failed due to poor timing, limited games, and confusion with the upcoming Sega Saturn.

Why did Sega CD fail?

- The Sega CD failed because of weak hardware, high cost, and a lack of compelling games.

Why did Sega Saturn fail?

- The Saturn failed due to its early launch, high price, and lack of developer support.

What killed the Dreamcast?

- The Dreamcast was killed by PlayStation 2’s dominance, lack of DVD support, and Sega’s damaged reputation.

Is Sega still in business today?

- Yes, Sega remains active as a successful software publisher and game developer.