In 2020, while pursuing a music minor, I was part of a weekly composer’s group at my college where we explored everything from orchestration techniques to modern scoring trends.

One week, I pitched the idea of giving a presentation on video game music—not just as background noise for gameplay, but as a serious and emerging platform for musical artistry.

Key Takeaways

- Video game music is a respected art form: live orchestras, academic programs, and awards prove its cultural impact.

- Licensed tracks shape emotion and setting: modern titles use needle drops to anchor mood, era, and story beats.

- Adaptive, looped scores drive immersion: dynamic layering and themes respond to player actions across gameplay states.

A few gamers in the group immediately understood, but many still viewed game soundtracks through an outdated 8-bit lens. Determined to change that perception, I prepared a short presentation showcasing the lush, emotional scores of Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy VIII.

The Table of Contents

Unfortunately, as the semester wore on, my talk was repeatedly pushed back in favor of other topics. By the time I graduated in spring 2022, the presentation never made it to the group—though the importance of video game music has only grown since then.

How My Journey into Video Game Music Began

Today, video game scoring is recognized as a legitimate discipline in prestigious programs like Berklee College of Music and the New England Conservatory; proof that what once felt niche is now shaping the future of modern composition.

proof that what once felt niche is now shaping the future of modern composition.

- From “background noise” to storytelling tool in modern games

- Academic validation through dedicated game composition courses

- Growing respect from critics, audiences, and live music venues

How My Journey into Video Game Music Began – Then and Now

If I were to make the same pitch to an undergraduate composing group at a random liberal arts college today, I believe it would receive a far more enthusiastic reception. In fact, video game music courses are now part of the curriculum at prestigious programs like Berklee College of Music and the New England Conservatory—signaling how far the medium has come in just a short time.

This growth is driven in part by the explosion of the casual gaming market, which has created a significant new source of work for emerging composers. Beyond job opportunities, video game composing has gained widespread respect from both audiences and critics.

One landmark moment came when Christopher Tin’s theme for Civilization IV, Baba Yetu, became the first piece of video game music to win a Grammy Award—an achievement earned six years after the game’s release, proving that great game soundtracks can stand the test of time.

- Work opportunities for new composers across indie and AAA

- Broader critical acclaim and awards recognition

Live Performances and the Cinematic Evolution of Video Game Music

The Distant Worlds tour has been bringing orchestral arrangements of Final Fantasy soundtracks to classical music venues around the globe since 2007, demonstrating the enduring appeal of these compositions.

demonstrating the enduring appeal of these compositions.

At the same time, bands like The Minibosses have built a loyal following with their progressive rock covers of video game themes from the Nintendo NES era.

Today, sheet music is readily available for many popular titles, and official video game soundtracks are often sold alongside—or even separately from—the games themselves.

This trend reflects a broader shift toward the cinematic capabilities of video games. As games have become more visually and sonically immersive, players increasingly seek out quiet, light-controlled spaces to fully appreciate both the narrative and the soundtrack during gameplay.

This merging of gameplay and cinematic presentation has brought games into spaces once reserved for traditional film and music experiences.

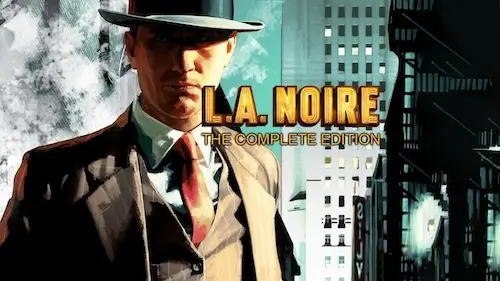

One notable milestone came in 2011 when L.A. Noire became the first video game officially featured at the prestigious Tribeca Film Festival, underscoring the growing recognition of video games as a legitimate art form.

- Orchestral tours and rock arrangements boost mainstream visibility

- Soundtracks and sheet music drive fan engagement beyond gameplay

- Cinematic presentation pushes games into arts & festival spaces

The Rise of Video Game Music as a Respected Art Form – Licensed Music in Games

Licensed music in video games can create impressions just as vivid and memorable as those in films. Some standout examples include Alan Wake II and its theatrical musical interludes; the nostalgic needle drops in Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy that bring an ‘80s playlist to life; the way “Take Me Home, Country Roads” became inseparably tied to the Fallout vibe; and pop mega-collabs in Fortnite that turn songs into shared cultural moments.

Licensed tracks also help establish a game’s mood, setting, and time period quickly and effectively. For instance, Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War leans on era-defining hits to immerse players in its historical backdrop, while Cyberpunk 2077 blends original synth scores with curated real-world artists to reinforce its neon-drenched world. The Last of Us Part II uses Pearl Jam’s “Future Days” as a narrative anchor, making it emotionally inseparable from the story.

- Mood-setting needle drops that deepen tone and atmosphere

- Period cues that instantly place players in time and culture

- Narrative motifs where a song becomes part of the character arc

Here is a cool video of Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder Performs Future Days

▶

▶

Prestigious Music Schools Now Teach Game Composition

Dismissing the quality of video games as an entertainment and artistic medium is becoming increasingly difficult—and this holds true for their music as much as for acting, graphics, narrative structure, or gameplay. A prime example is Journey composer Austin Wintory, who served as the composer-in-residence for the Boulder Symphony in 2011, underscoring the growing respect for video game composition within the broader music community.

Throughout this article, I’ve compared video game music to film scoring because it’s a useful framework for understanding the artistry involved. However, games also present unique musical challenges and opportunities—such as creating dynamic, adaptive soundtracks that respond to player actions—making them a distinct and exciting frontier for composers.

- Growing institutional recognition of game scoring

- Composers bridging concert halls and console halls

The Unique Challenges of Looped and Adaptive Video Game Music

Unlike most film scores, which are designed to play over a specific scene for a precise amount of time, much video game music must be able to loop seamlessly or adapt to multiple gameplay situations without feeling repetitive or out of place.

seamlessly or adapt to multiple gameplay situations without feeling repetitive or out of place.

This presents unique creative challenges—how do you compose a track that works across diverse scenarios? How do you create a world map theme that won’t drive players mad after twenty hours of play?

- Seamless looping that stays fresh over long play sessions

- Adaptive layering that reacts to combat, exploration, or story beats

- Thematic cohesion across menus, maps, and boss encounters

These challenges also open the door to creative opportunities. Looping or adaptive music can subtly connect moments in a game’s narrative, encouraging players to draw comparisons between situations that might otherwise feel unrelated.

- Musical storytelling that threads motifs across gameplay states

- Player-driven pacing where the score breathes with exploration/combat

This level of musical storytelling is one of the reasons video game composition continues to gain respect, especially compared to a dozen years ago when I was still trying to convince fellow composers that the PS1 Final Fantasy soundtracks marked the beginning of something truly important. Even now, we are only scratching the surface of what music in games can achieve.

The Retro Wrap Up – The Future Soundtrack of Gaming

From my early attempts to convince fellow composers of the value of video game music to the thriving, globally recognized art form it is today, one thing has remained constant: great game music has the power to tell stories, shape emotions, and transport players in ways few other mediums can.

Whether it’s a sweeping orchestral score, a perfectly timed licensed track, or a cleverly adaptive theme, these soundscapes are now as integral to gaming as visuals or gameplay mechanics.

As technology advances and the line between film, music, and games continues to blur, composers will have more tools—and more creative freedom—than ever before. The next great gaming memories we make may very well be carried on a melody that stays with us for years to come.

What are your favorite video game soundtracks? Share them in the comments below, and check out our related guides to discover even more iconic game music moments.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What is the importance of music in video games?

- Music in video games sets the tone, enhances immersion, and can create emotional connections that elevate the overall player experience.

How is music used in video games?

- Video games use music to build atmosphere, guide player emotions, signal events, and enhance storytelling through thematic scoring.

What is the difference between film music and video game music?

- Film music is composed for fixed scenes, while video game music must often loop, adapt, and respond dynamically to player actions.

What makes a good video game soundtrack?

- A good video game soundtrack fits the game’s world, is memorable without being distracting, and supports both gameplay and narrative flow.

How do composers create music for video games?

- Composers design game music using adaptive, looping, and thematic techniques that align with gameplay mechanics and emotional beats.